Domain-Driven Design

The Domain-Driven Design (DDD) is an architecture style for building software systems where business requirements are clearly stated and separated from the surrounding application or infrastructure concerns. Some argue that microservice architecture is true only with DDD, although that might be a bit of an overstatement in my opinion.

The main goal of DDD is to make software more maintainable, to make it less complex to deal with. Its focus on the Domain requires a bit of a shift in how we think of software development. Using DDD might actually help to “discover” the domain properly, highlighting key entities (aggregate roots) and their invariants, together with bounds of these entities.

Bounded Context and Sub-Domains

As part of DDD, we identify Subdomains that take part in our system. Subdomain is a subset of some larger Domain. The terms are rather fuzzy. Every subdomain is some domain itself after all. Domains and subdomains are a hierarchical concept.

When we design DDD-compliant system, the domain is the general problem we’re trying to solve, let’s say “Monitoring of IoT Platform Instances”. This great domain may be splitted into smaller concerns - subdomains:

- users management

- platforms management

- notifications

- etc.

A Bounded Context represents a linguistic boundary within or across subdomains. Often, a Bounded Context is aligned with a Subdomain. The difference between these two concepts is as follows:

- a Subdomain is in the Problem Space.

- a Bounded Context is in the Solution Space.

So, a given bounded context is a proposed solution to a problem within some subdomain(s). Ideally, one bounded context should cover one sub-domain. For larger sub-domain we could have many bounded contexts covering it. The relation between Sub-domain and Bounded Context is a bit fuzzy then.

In a typical project, there will be many bounded contexts. Ideally, each of them should be developed by a different team. Each would also use a separate persistence data store.

Bounded Context is made up of all the aspects that are drived by its model:

- the domain model itself

- the application that uses the model

- database schema that persists the model objects

Bounded Context vs Microservice

There isn’t a 1:1 relation between a bounded context and a microservice. A single bounded context could be served by multiple microservices. For example, one microservice could be in a form of an HTTP API, serving requests. Another microservice could be a listener on some bus. Both could work on the same database, but they’d work on a different parts of the overall responsibility of the bounded context. However, they’d both use on Ubiquitous Language set, and a single Domain layer.

Ubiquitous Language

The most important part of DDD is the establishment of the Ubiquitous Language - an agreed vocabulary (between developers and domain experts) that will be used to describe various entities in the Bounded Contexts. It should be used everywhere in the project: code, diagrams, discussions, etc.

Every bounded context will have its own ubiquitous language.

Context Maps

The namings in different Bounded Contexts and their relations is what defines Context Maps. It could be that different Bounded Contexts use the same name for different entities. It could also happen that different bounded context would model the same entity differently (like a Customer in Appointment Scheduler context and Customer in the Billing context).

A Context Map clearly shows what a given entity is represented by in another context.

Synchronization

Different bounded context may model data for the same physical entity. For example, Patient Management context and scheduling context may contain the Patient entity. Probably, the one in the Patient Management context will be more detailed. Also, probably that one will allow for various modifications. E.g., we could change the patient’s name. The other contexts that model the Patient should be notified about this change. E.g., it could be done via some message bus. The Patient Management service would publish a message about the change, and all other interested services would be listeners.

This approach obviously complicates the overall system. It also introduces Eventual Consistency (which really is unavoidable in distributed systems). Therefore, it’s important to consider what data is truly needed in a given bounded context. When referencing entities from different bounded context, the best case scenario is to reference it just by its ID. IDs are immutable and they will not change. Any additional data (that can change in time) will probably require us to setup the synchronization mechanism (via Domain Events). Note that referencing just the ID might also not solve the problem entirely. We might have a case where a given entity gets removed from the other Bounded Context. Its removal might need to be propagated to other bounded contexts as well.

Domain Model

Designing our domain model is crucial. According to Eric Evans:

The domain is the heart of business software.

Another point is that models evolve over time. Our initial assumptions can be often invalidated as we progress in understanding the domain.

In our modeling, we should focus on the behaviours of the models. To find such behaviours, we need to look at all the possible events that may occur in the system - those events are basically the use-cases that the solution is expected to fulfill. Some examples of these events could be (in medical clinic system):

- add a new patient

- schedule a visit

- move a visit to another date

Rich Domain Models

DDD encourages the use of Rich Domain Models, opposed to the Anemic Domain Models. Anemic models are simply classes that are DTOs, or classes with very little logic inside of them.

Often in our programs we have DTO classes and other service classes that act on these DTOs, potentially modifying them. This is an anti-pattern in the DDD world. Martin Fowler argues that this is even an anti-pattern in the OOP sense, since OOP is supposed to merge data and behaviour together.

Entities

These are objects defined by their identity. That means that every instance of an Entity is unique, it has its own key identifier. That ID should be unique. When a given Entity is contained within some Aggregate Root, its ID must be unique only within its Aggregate Root instance.

Sometimes it might not be that easy to understand whether a givne thing is an Entity or just a Value Object. A good way to figure that out is to consider whether that “thing” has some lifecycle. If there are business cases where the thing gets modified (while upholding its identity), it most likely is an Entity.

Potential candidates for entities in Medical Clinic Management system would be:

- Patient

- Doctor

- Room

- Appointment

An entity should always be in the valid state (to uphold its invariants). Hence any modification of an entity (or its creation) should contain various guard clauses that make sure the operation can be done. For example, before I rename a Patient, I should make sure that the new name is not empty.

Entities also contain Domain Events. These may be used to inform other parts of the system of changes.

Value Objects

Identity of Value Objects is based on composition of its values. They’re immutable. Whenever some part of value object chages, a new object should get created, while the old one gets disposed. Value objects may contain methods (without side-effects). Value Objects represent things that are not defined in the domain. They rather describe/measure/quantify something in the domain somehow. Examples include:

- money

- date range

An instance of a value object does not represent any unique entity, it’s just a set of information representing something in our domain.

It’s recommended to first consider Value Object when deciding whether to use Entity or Value Object for a given thing.

Date types are a great example of value objects.

Domain Services

Logic/behaviour that doesn’t fit into Entities or Value Objects goes into separate classes called Domain Services. Such services often deal with different kinds of entities/value objects. For example, they could orchestrate some workflow.

Before creating a service, we should make sure that the logic we’re adding doesn’t fit into any of the existing domain elements (entities/value objects).

Domain Services are often a good artifact to use to avoid placing domain login in the Application layer.

Aggregates

When building our Entities we will often end up with Aggregate entities, that is, entities that are linked with other entities or value objects.

Citing Martin Fowler:

A DDD aggregate is a cluster of domain objects that can be treated as a single unit. An example may be an order and its line-items, these will be separate objects, but it’s useful to treat the order (together with its line items) as a single aggregate.

Aggregate Root

Aggreagate Root is an entry point of an aggregate that “defines” the aggregate as a whole.

It’s easy to design Aggreagate Root improperly or not optimally. Often we arrive at the valid design iteratively, starting from some initial assumptions. As we learn more about the domain (which evolves!), our model will evolve as well. One way to find out what is an aggregate root, we need to look at individual components and think if the removal of a given component would result in removal of its contained components (cascading delete). If it would, that’s probably an Aggregate Root.

Aggregate Root is like a central entity that defines it completely. It should allow us to keep the whole object in a valid state (enforcing invariants). It creates a consistency boundary, within which those invariants are enforced. Aggregate Root should also have transactional consistency. Consistency of things outside of the aggregate is irrelevant.

Aggregater Root shouldn’t be too large (to stay performant, since loading lots of internal entities might be heavy), and should not be too small (to avoid anemic model and failing to protect invariants). We shold prefer smaller aggregates though (as big as they need to be and not bigger). Larger aggregates make consistency boundary and transaction scope large as well.

A simple example of keeping invariants is an Order aggregate root that should make sure the number of Items within it does not cross some

business-defined limit.

We should access/modify the aggregate only throught the Aggregate Root. Internal entities (non-agregate roots) should stay private in the Aggregate Root, and they should not be referenced outside of the Aggregate Root (unless it’s temporary within some process execution). Accessing those internal entites should be only via the Aggregate Root instance. Aggreagate Root may also hold reference to some other Aggregate Root (either as a reference to object or just by the ID).

A single bounded context or domain may contain a few Aggregate Roots.

Transactions

When a new business requirement comes in that requires you to update a few aggregate roots instances in a single transaction, it is worth to make sure that the model itself is still valid. It might be, that the new business requirement is actually an update to the Ubiquitous Language, and a new Aggregate Root should get introduced.

For example, if we have some Item entity (aggregate root), and we get a requirement to make sure

that when updating one Item, we also need to update some other Item, try to discuss with the Domain

Expert what this pair of items actually represents. Maybe there should be a new Aggregate Root

(like ItemsPair) introduced in the system and Item itself should not be Aggregate Root anymore? With such new Aggregate Root in place, we will manage

Items from a different level (new repository), and we can keep the “one aggregate root per

transaction” rule alive.

It might also be that the new requirement introduces more issues than it gives benefit. Maybe the requirement should be changed to keep the system maintainable.

There will be cases where one Aggregate Root istance has references to other Aggregate Roots. Even then, we shold try to upkeep the “one transaction per aggregate” rule. Either update the referred aggregate or the reference holder in a transaction, but not both. Use domain events to propagate changes, making sure the whole thing is eventually consistent.

Transactions should be managed in the Application Layer.

Associations

DDD encourages one-way relations between entities. It’s popular in Entity Framework to define navigation properties in both ways. It turns out it’s not always needed. It makes entities more complex. By default, we should start our modeling with uni-directional relationships and switch to bi-directional ones only when necessary.

It still is OK to keep an identifier of the other entity (like a foreign key) in the “child” entity.

When thinking to associate two aggregates, it’s worth to remember what defines an Aggregate Root:

We need to look at individual components and think if the removal of a given component would result in removal of its contained components. If it would, that’s probably an Aggregate Root.

If removal of our root should not result in the removal of linked aggregates, possibly we don’t need to include these children as “Navigation Properties”. Instead, maybe just an ID of that other entitiy is enough.

An example is an aggregate called Appointment. It would contain references to:

- Patient

- Doctor

However, since removing an Appointment should not remove Patient and Doctor, it makes sense to reference these just by ID, not by Navigation Properites.

Shared Kernel

In DDD, a Shared Kernel is code that is used between different bounded context. It’s basically a kind of project that .NET developers often call Common. The shared part should be as stable as possible. Changes in that code will affect a lot of places.

Repositories

Repository pattern is a well-known approach and it is also used outside of DDD. DDD-specific fact is that only the Aggregate Roots should have their repositories. Other entities should be accessed via their aggregate roots.

There are two ways to create an Aggregate instance:

- via its constructor/factory method - when instantiating a new instance with a brand new ID

- via repository - when reconstituing an existing instance that was previously created. It also happens via cosntructor/factory, but from the Application Layer perspective, the repository is the source of the object.

Repository might have methods to return other things than just Aggreagate Root instances. Depending on the businesss cases, we might need things such as:

- counts of objects

- some composition of parts of different aggregate root(s) - these compositions would be Value Objects

The second case from the list above is a bit of a code smell though. When we employ such tactics, it might point at some issue with our Domain modeling. It could be that our aggregates are not defined properly. Such approaches are most often used for performance reasons. Even when you decide to add such repository method, make sure that the data that gets exposed is a data that you’d be able to navigate to if you had a reference to the Aggregate Root itself. Otherwise, you might break the consistency boundary.

A repository could use another sub-repository to fetch some additional data.

Domain Events

There are two kinds of events:

- in-domain - Domain Events (in-process)

- across domains/bounded contexts - Integration Events

Domain Events

Domain Events are raised when something happens in the domain that could be of interest to the other pieces of our application (but in the same process!). They should be describable in the Ubiquitous Language and their names should correspond to that. The naming should be in the past tense, since the events will always inform about something that has already happened. Some examples:

- Client Registered

- Appointment Scheduled

In code, each event is a separate class. It should iunclude the set of information that might be interesting for a given event.

Dispatching Events

Events should be dispatched from the Domain layer. Entities or Domain Serves could emit them.

Events may have multiple handlers. Normally, the order of their execution should not matter.

Integration Events

These events are the way to share information that something happens across domains or applications. They could include more information than the Domain Events since the receiver of the event might not be able to get these information on its own. For example, instead of just sharing the ID of some changed entity, we would also share some more defining properties, like a Name. It could also happen that the event handler would have to get back to the source service to ask for more details. We might not want that, especially if there’ll be a lot of events, or a lot of handlers.

Integration Events often use some kind of message bus, like Azure Service Bus.

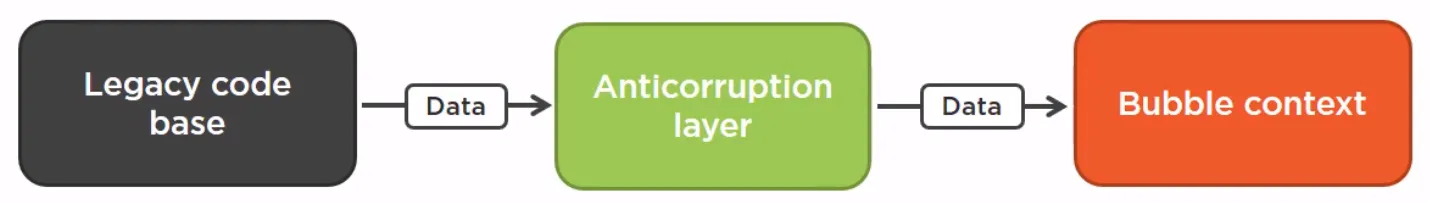

Anti-Corruption Layer

It often happens that we have to integrate with systems that are outside of our control. Such systems will most likely use a different modeling than ours. In such cases, Anti-Corruption Layers help us to create a kind of mapper between our domains and the other systems. Such layers are basically like Adapters.

It could also work the other way round. We could have a “legacy” system that we want to update to integrate with a “well-designed” DDD project. In order not to introduce the new concepts into legacy codebase, we could create an ACL layer (like some set of services) that will communicate with our DDD system properly and return the data as the legacy system expects.

In practice, ACL is often just a mapper/translator kind of class. In more complex scenarios, it could be a separate process with endpoints that reach out to the legacy system and translate the responses to our Ubiquitous Language.